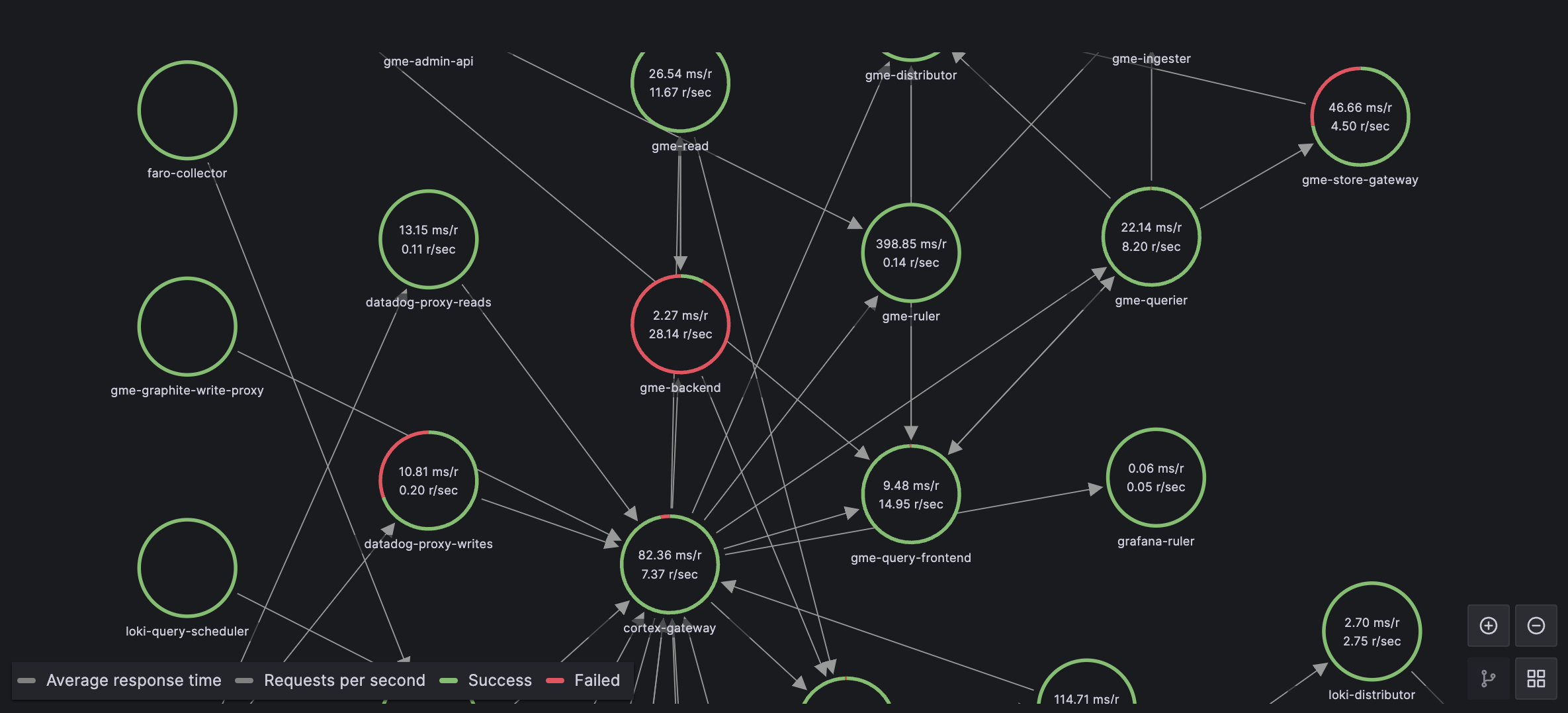

Introducing Metric Registry: a live,

searchable catalog of 3,700+ observability (and rapidly growing) metrics

extracted directly from source repositories across the OpenTelemetry,

Prometheus, and Kubernetes ecosystems, including cloud provider metrics.

Metric Registry is open source and built to stay current automatically as

projects evolve.

What you can do today with Metric Registry

Search across your entire observability stack. Find metrics by name,

description, or component, whether you're looking for HTTP-related histograms

or database connection metrics.

Understand what metrics actually exist. The registry covers 15 sources

including OpenTelemetry Collector receivers, Prometheus exporters (PostgreSQL,

Redis, MySQL, MongoDB, Kafka), Kubernetes metrics (kube-state-metrics,

cAdvisor), and LLM observability libraries.

See which metrics follow standards. Each metric shows whether it complies

with OpenTelemetry Semantic Conventions, helping you understand what's

standardized versus custom.

Trace back to the source. Every metric links to its origin: the repository,

file path, and commit hash. When you need to understand a metric's exact

definition, you can go straight to the source.

Trust the data. Metrics are extracted automatically from source code and

official metadata files, and the registry refreshes nightly to stay current as

projects evolve.

Can't find what you're looking for? Open an issue or better yet, submit a

PR to add new sources or improve existing extractors.

Sources already indexed

| Category | Sources |

|---|

| OpenTelemetry | Collector Contrib, Semantic Conventions, Python, Java, JavaScript |

| Prometheus | node_exporter, postgres_exporter, redis_exporter, mysql_exporter, mongodb_exporter, kafka_exporter |

| Kubernetes | kube-state-metrics, cAdvisor |

| LLM Observability | OpenLLMetry, OpenLIT |

| CloudWatch | RDS, ALB, DynamoDB, Lambda, EC2, S3, SQS, API Gateway |