The Multi-Cloud Design: Engineering your code for Portability

In our previous post on Cloud-Native foundations, we explored why running on one cloud isn't lock-in—but designing for one cloud is. Now let's look at how to implement that portability.

Portability is not defined by the ability to run everywhere simultaneously, as that is often a path toward over-engineering. It is, more accurately, a function of reversibility. It provides the technical confidence that if a migration becomes necessary, the system can support it. This quality is not derived from a specific cloud provider, but rather from the deliberate layering of code and environment. While many teams focus on the destination of their deployment, true portability is found in the methodology of the build.

The Two Fronts: Application Layer vs Environment Layer

To keep your options open, you have to work on two fronts.

First, the Application Layer. This is your domain logic. It should be blissfully unaware of whether it's talking to a proprietary cloud queue or a local database. Second, the Environment Layer. This is your config, the "container" your code lives in. It needs to be reproducible and declarative. If an environment cannot be recreated with a single command, the system relies on luck rather than automation.

Most systems don't fail at the deployment stage. They fail in the code. When your business logic starts calling proprietary SDKs directly, you've stopped building a product and started building a feature for your cloud provider. You might be "on Kubernetes," but if your code is married to a specific vendor's identity service or database quirks, you're stuck.

Designing for a Cloud is the Trap: The Cost of Vendor Lock-In

There is no harm in running on one cloud. The risk is making irreversible design decisions. If you build on open interfaces, you can happily stay on one provider for years while still keeping the power to:

- Spin up a secondary site during a regional meltdown.

- Shift workloads when the "committed spend" math stops adding up.

- Actually negotiate your contract because you have a credible exit.

Portability provides strategic leverage

Kafka as a Library: The Interface-First Mindset

Take Kafka. It's a great example because it has evolved from a tool into a protocol. If your app depends on the Kafka API rather than a specific vendor's implementation, Kafka effectively becomes a library. Whether you're using self-hosted Apache Kafka, a managed service, or something like Redpanda, your producers and consumers don't care. Only the plumbing changes.

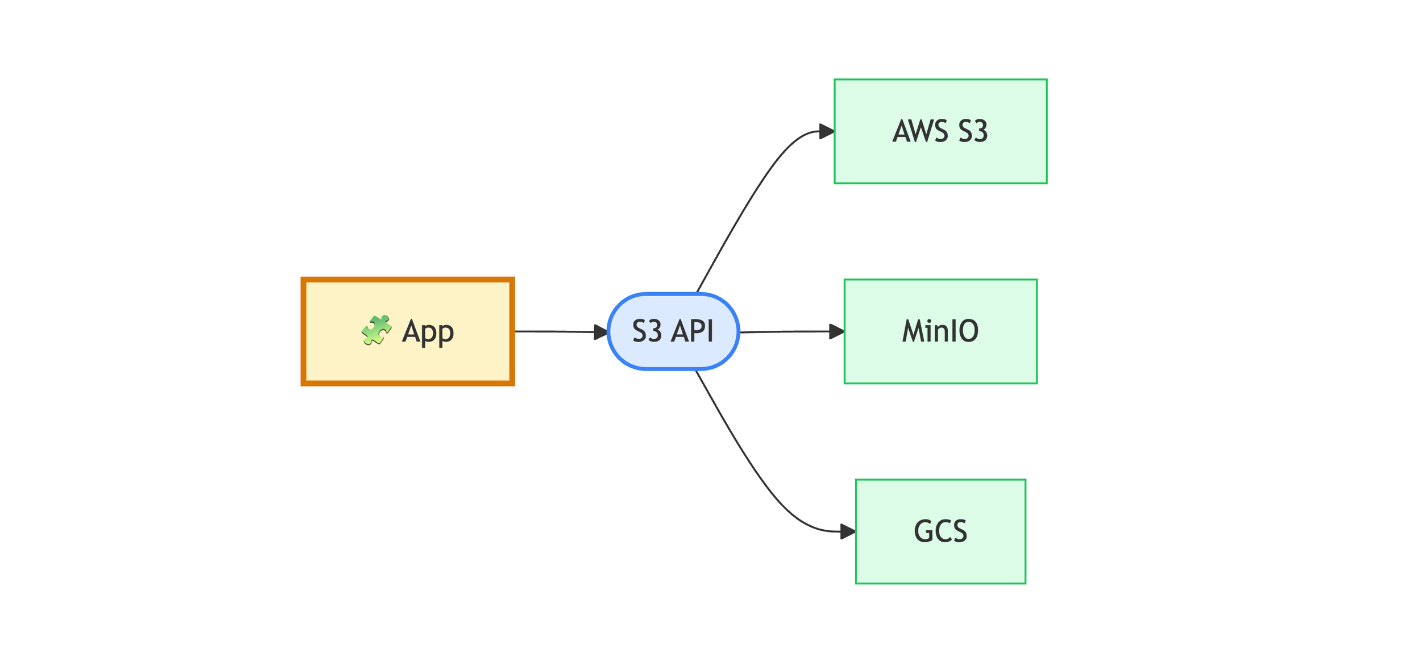

This pattern is everywhere if you look for it:

-

Databases: Postgres and MySQL protocols.

-

Identity: OAuth and OIDC.

-

Observability: OpenTelemetry.

-

Storage: The S3 API.

The CNCF landscape is more than a list of tools; it's a map of the interfaces that won. When you see multiple mature implementations for the same protocol, that's your green light to build. It sets the pace for the entire ecosystem, signaling to vendors the language the ecosystem now speaks.

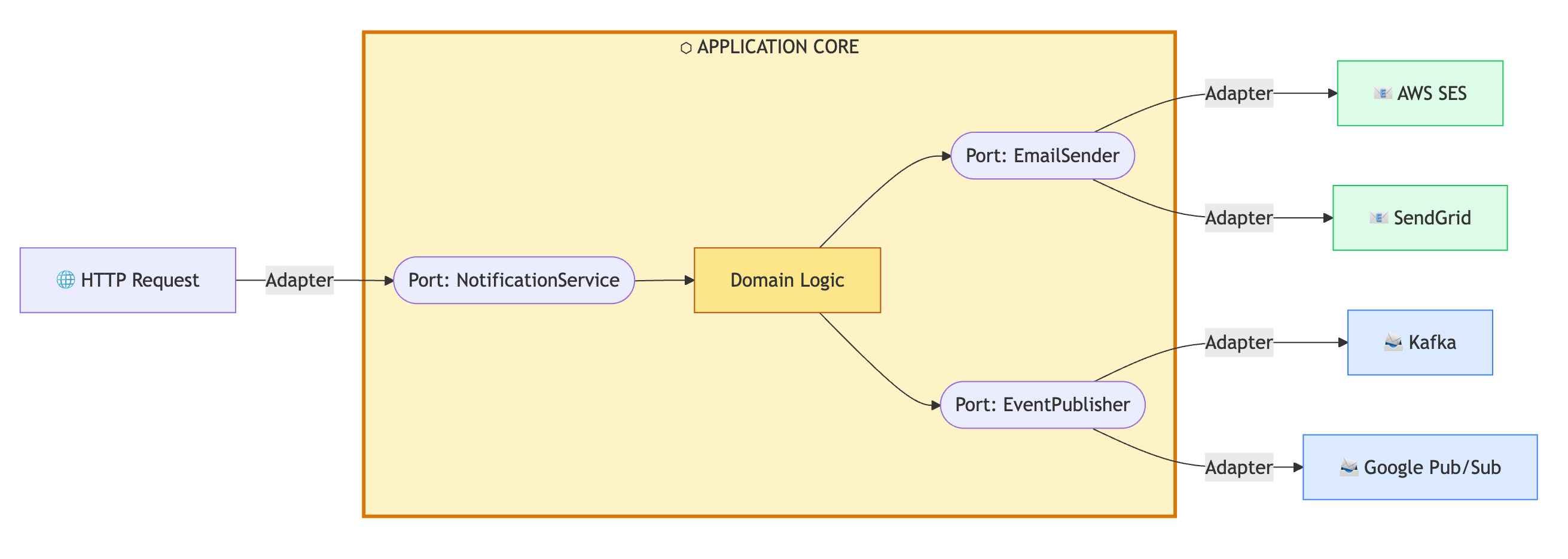

Business Logic Should Be Ignorant: The Adapter Pattern

Portability fails when your code knows too much. The rule is simple: Your business logic should not care where it runs.

This is where "ports and adapters" (hexagonal architecture) moves from theory to practical survival. Your domain talks to an interface; your infrastructure lives behind an adapter.

Yes, this costs something. You pay in abstraction. But 'abstract' shouldn't mean 'complex.' You aren't introducing a heavy new component or a fragile moving part; you're just building a wrapper. This is the adapter pattern in its most practical form. The 'adapter' in a ports and adapters architecture. It's the difference between hard-wiring your logic into a vendor's proprietary API and simply translating their contract into your own domain schema. This minor friction today prevents a total collision during a high-cost migration later.

While portability requires consistent daily investment, it mitigates the significant, sudden costs associated with vendor lock-in..

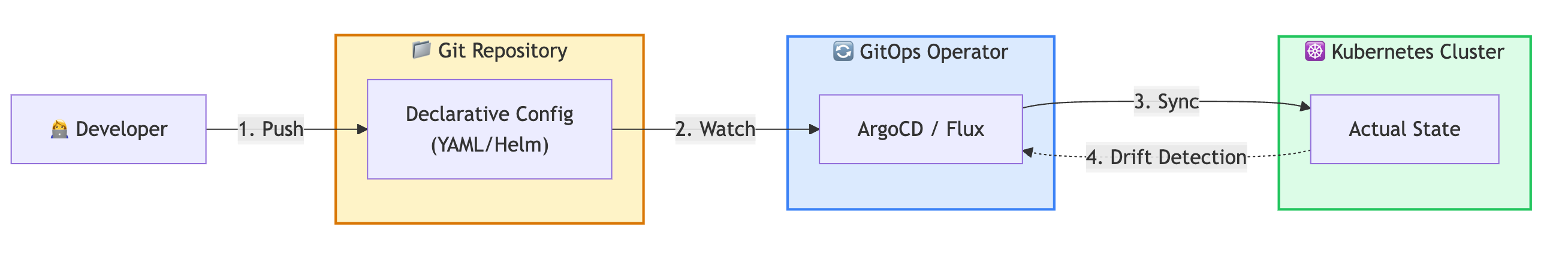

Intent vs. Instructions: GitOps for Reproducibility

Layered code is insufficient if standing up in a new environment requires tribal knowledge. Infrastructure must be reproducible, which is the core of GitOps. Storing intent is superior to storing instructions, because describing "what" must exist is more durable than the "how" of a dashboard. Mapping this intent to specific cloud APIs is a one-time configuration task that moves cloud-specific friction out of the architecture and into a manageable layer.

GitOps makes this real by storing your intent in Git. Now, let's be clear: this isn't magic. You still have to do the one-time work of mapping that intent to a specific cloud's APIs whether that's configuring a Crossplane provider, a Terraform module, or a specific Ingress controller. Think of it as installing a driver. You do the plumbing once so that your application logic doesn't have to care about it. Once those mappings are in place, the workflow is identical: commit, push, sync. You've successfully moved the cloud-specific friction out of your architecture and into a manageable configuration layer. This is what makes true multi-cloud and hybrid deployments practical.

You Don't Need to Move, You Just Need to Know You Can

At the end of the day, some decisions are hard to undo. Choosing open interfaces and declarative configs makes them easier.

It gives you the room to respond to outages, control your costs, and meet new compliance hurdles without breaking the company.

You don't need to move often or move at all. You just need to know that the door isn't locked from the outside. That's the real value of avoiding vendor lock-in.

What's Next?

In the next post, we'll dig into the stack itself: which protocols actually preserve your freedom, and which ones are "open" in name only.

Related Reading

- The Cloud-Native Foundation Layer — Part 1: why running on one cloud isn't lock-in, but designing for one is

- Why Unified Observability Matters — Applying vendor-neutral principles to your monitoring stack

- Observability Theatre — The cost of fragmented tooling and how to escape it